Sailing Tahiti to Australia | Month 1 Preparations

by Jana Gamble

Welcome!

We are a family of four: Grant (dad), Jana (mom), Jack (16) and Stella/Ellie (15). We just finished an 8-month tour of the U.S. and Mexico in Thelma & Louise, our Monaco Diplomat motorhome and Jeep Wrangler. This is the first month of our next chapter, a sailing trip from Tahiti, French Polynesia to Australia. We arrived in Tahiti in June 2021 to take ownership of a new-to-us boat, “Hanavave,” a 2002 Catamaran Athena 38 Fountaine Pajot that is to be our new home for the foreseeable future. Hanavave is the name of a very picturesque bay in the Marquesas, an island group in French Polynesia, northeast of Tahiti.

We are a family of four: Grant (dad), Jana (mom), Jack (16) and Stella/Ellie (15). We just finished an 8-month tour of the U.S. and Mexico in Thelma & Louise, our Monaco Diplomat motorhome and Jeep Wrangler. This is the first month of our next chapter, a sailing trip from Tahiti, French Polynesia to Australia. We arrived in Tahiti in June 2021 to take ownership of a new-to-us boat, “Hanavave,” a 2002 Catamaran Athena 38 Fountaine Pajot that is to be our new home for the foreseeable future. Hanavave is the name of a very picturesque bay in the Marquesas, an island group in French Polynesia, northeast of Tahiti.

Getting There

Grant and Jack were scheduled to leave Seattle for Tahiti in the early morning on Saturday, June 12, to pick up our new-to-us boat, “Hanavave.” We bought Hanavave from Frank, a very nice German man who had sailed her from Germany to Tahiti with the goal of ending in Australia, but his voyage got cut short by COVID and its subsequent travel restrictions and port closures. We bought the boat remotely, sight unseen, which means that there were likely going to be dreaded surprises which Grant and Jack were to uncover upon their arrival. Because Frank had been stuck in Tahiti for quite a while, there was a lot of deferred maintenance and we were able to negotiate a very favorable price, knowing that we would have a fair bit of work to do before we would be able to set sail.

Our plan was to fix Hanavave up, leave Tahiti and island hop all the way to Australia, some 3,270 nautical miles (about 5,000 regular miles) away. If sailed directly the trip would take about a month at sea, but we are “reasonable” people and planned on taking our time and exploring French Polynesia, Cook Islands, Tonga, Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu and anywhere else that struck our fancy along the way. Ellie and I were staying in Seattle for an extra week so that we could have some quality girl time together and give Grant and Jack the same as they started on the major TLC that Hanavave would need.

Our plan was to fix Hanavave up, leave Tahiti and island hop all the way to Australia, some 3,270 nautical miles (about 5,000 regular miles) away. If sailed directly the trip would take about a month at sea, but we are “reasonable” people and planned on taking our time and exploring French Polynesia, Cook Islands, Tonga, Samoa, Fiji, Vanuatu and anywhere else that struck our fancy along the way. Ellie and I were staying in Seattle for an extra week so that we could have some quality girl time together and give Grant and Jack the same as they started on the major TLC that Hanavave would need.

After spending every waking hour together for the last eight months traveling the U.S. and Mexico in Thelma, I felt a knot tightening in my stomach as the boys’ departure date was nearing. I didn’t want our family to separate and be so far away from each other, but I also knew that my anxiety was natural, and the benefits of the brief separation would far outweigh any anxieties.

Our plan was to fix Hanavave up, leave Tahiti and island hop all the way to Australia, some 3,270 nautical miles (about 5,000 miles) away.

What About Our Puppies?

We had said goodbye to Thelma two weeks before and shortly after, we had to drop off our puppies, 9-year-old Labradoodles Mackie and Paigie and 3-year-old Great Dane Phoebe, at a kennel in Washington state. After countless hours of trying out every single scenario, we determined that there was no way to take our puppies with us to French Polynesia or anywhere else in the South Pacific. Grant spent countless hours looking for airlines that would fly them and countries that would accept them, to no avail. Due to COVID and limited flights, there simply isn’t a way at this time. Mackie, Paigie and Phoebe are staying with Colleen, a very sweet lady with a beautiful outdoor/indoor kennel in her back yard that is spotlessly maintained. She clearly loves the dogs she takes care of, which gave us a great sense of comfort when we first visited her.

We had said goodbye to Thelma two weeks before and shortly after, we had to drop off our puppies, 9-year-old Labradoodles Mackie and Paigie and 3-year-old Great Dane Phoebe, at a kennel in Washington state. After countless hours of trying out every single scenario, we determined that there was no way to take our puppies with us to French Polynesia or anywhere else in the South Pacific. Grant spent countless hours looking for airlines that would fly them and countries that would accept them, to no avail. Due to COVID and limited flights, there simply isn’t a way at this time. Mackie, Paigie and Phoebe are staying with Colleen, a very sweet lady with a beautiful outdoor/indoor kennel in her back yard that is spotlessly maintained. She clearly loves the dogs she takes care of, which gave us a great sense of comfort when we first visited her.

Leaving the puppies for a few months was a very difficult decision for us, but it ended up being our only option. Colleen will eventually put Mackie, Paigie and Phoebe on a plane to Australia to be reunited with us once we arrive. In the meantime, we will have to settle for regular updates and weekly photos of our babies. We are happy to report that they are adjusting very well and are enjoying having a yard for the first time in 8 months. Having lived on the boat for a month now, we cannot imagine Mackie, Paigie and Phoebe to function here happily. In the end, staying with Colleen has turned out to be for the best.

Importing dogs into Australia is another extremely difficult and expensive undertaking, but Grant spent months working on the process and finally got the dogs to a point where they are immigration worthy. But first, they will have to spend 10 days in quarantine in Melbourne and get re-tested for all the various and sometimes obscure diseases and conditions that Australian authorities do not allow into the country. Fair enough, but it does make them the most difficult country for importing dogs. Unwilling to leave our puppies behind, we accepted this process as an integral part of our Australian migration.

Leaving the puppies for a few months was a very difficult decision, but it ended up being our only option.

The Joys of International Travel During COVID

While they are a very minute minority, there have been a couple of people who objected to our traveling during COVID, labeling it as irresponsible and selfish. We of course disagree with this misguided characterization of our travel, but fully expect there to be more people who feel this way and don’t express their view in order to avoid conflict or a tough conversation. We felt that it may be worthwhile to address this issue up front, because after 8 months on the road, there is no doubt in our mind that traveling during COVID was the right choice.

We have minimized our risk of exposure by following all of the CDC recommendations, avoiding tourist traps, not eating in restaurants and wearing masks. Given these practices, our risk of exposure hasn’t been much different to being at home. We also live a very healthy lifestyle, so our immune systems are relatively robust. To see how we’ve tried to stay healthy and safe while traveling during COVID, you can read this article.

However, international travel brings a myriad of new complexities and unknowns, making the trip preparation that much more complex and stressful. Prior to departure, we had to complete individual applications to enter Tahiti called “ETIS,” and wait for the authorities to process them and send us QR codes which would then be required to board the plane and to pass through immigrations once in Tahiti. Grant submitted the ETIS applications well in advance of all of our departures, but his approval only arrived 12 hours prior to his and Jack’s scheduled departure. However, Jack’s approval never arrived.

In the meantime, Grant contacted the authorities directly to try and get some answers, but was largely met with indifference, rudeness, and: “You have to respect our deadlines,” which of course we had. The language barrier also proved to be an issue, as all communication and paperwork was in French and even the authorities either didn’t speak English or had very little desire to. Our language abilities include Spanish, Czech, English and Australian, so we were out of luck and had to rely on Google translate, a comical and often futile exercise.

As a last resort, Grant called the U.S. Embassy in Tahiti. When someone finally answered the phone on his third and last attempt, Grant asked: “Do you speak English?,” to which the man on the other side sarcastically replied: “No, why would anyone at the U.S. Embassy speak English?!” Grant laughed him off and after explaining our situation, the man, named Christopher, told him that as of yesterday, the ETIS forms were no longer necessary. This was obviously a huge relief, but we wondered why the immigration authorities didn’t tell us the same when we enquired about Jack’s application status.

We also had to complete COVID PCR tests within 36 hours of departure, which added a relatively large cost to our trip at about $200 per person. We found a clinic and made appointments for the appropriate times in order to satisfy this requirement. This step went very smoothly, and we even got our bonus brain cleanings in the process.

On Saturday, June 12, Grant and Jack got up at 4am to make their way to the Seattle Airport for their 7:30 am departure to Tahiti via San Francisco, still without Jack’s ETIS QR code, but hoping that Christopher, the U.S. Embassy agent was correct, and they would be allowed to fly. Once at the gate for the Tahiti flight, all passengers had to line up for a paperwork check, conducted by a couple of airline agents. Grant and Jack got through without anyone asking to see their ETIS QR codes which was a huge relief, but they still wondered how things would go once they had to clear immigrations in Tahiti.

On Saturday, June 12, Grant and Jack got up at 4am to make their way to the Seattle Airport for their 7:30 am departure to Tahiti via San Francisco, still without Jack’s ETIS QR code, but hoping that Christopher, the U.S. Embassy agent was correct, and they would be allowed to fly. Once at the gate for the Tahiti flight, all passengers had to line up for a paperwork check, conducted by a couple of airline agents. Grant and Jack got through without anyone asking to see their ETIS QR codes which was a huge relief, but they still wondered how things would go once they had to clear immigrations in Tahiti.

The flight from San Francisco to Tahiti was about 8 hours long, which is similar to going to Europe from the East Coast of the U.S., depending on where you’re going. The boys’ flight wasn’t full, so they had three seats to themselves, a much welcome bonus after waking up at 4am.

Upon their arrival in Tahiti, they got flagged down by an official asking about Jack’s ETIS status. Grant explained the situation and they magically let them through without any further questions. Once through immigrations and customs, each passenger was administered a rapid COVID test and after waiting 20 minutes and collecting their bags, they exited the airport, provided their tests came out clear. It was about 8:30pm as they stepped out of the airport into the warm, humid Tahiti air. They were picked up by Arnaud, a sales broker for the yacht brokerage company, and headed for Marina Taina with much excitement and anticipation.

Arnaud is a 59-year-old avid sailor and diver who came to Tahiti from France a long time ago. His English is good enough and he is very friendly and welcoming. He drove Grant and Jack about 20 minutes to Marina Taina, where Hanavave is moored. Since they were now in the Southern Hemisphere, it was winter in French Polynesia and pitch black by then. Arnaud took Grant, Jack and their 4 large waterproof bags containing everything from clothes to a large inverter and snorkeling gear to our boat in a dinghy, which was about a 10-15 minute ride.

The boys arrived to Hanavave both exhausted and excited, but their first impression was that of shock once they saw the amount of stuff everywhere. It was after 9pm by now and too late to try to sort through anything, so they decided to sleep outside on the trampoline, located at the front of the boat.

The boys arrived to Hanavave both exhausted and excited, but their first impression was that of shock once they saw the amount of stuff everywhere.

Bienvenue à Tahiti

The next morning, Grant woke up very early to astoundingly idyllic surroundings Hanavave was floating in crystal clear turquoise water with the island of Tahiti portside and the small and paradise-like island of Moorea in the distance on the starboard side. The rest of the view was that of a seemingly infinite blue ocean.

Marina Taina is located inside a lagoon lined by a coral reef, which makes it look like there is a surf break in the middle of the ocean that surrounds the many bobbing boats, with waves crashing and mist flying through the air in the distance. The water is two-toned: a darker ultramarine in the deeper sections where the boats are moored and a bright turquoise in the shallows near the reef, with bomboras and smaller coral gardens interspersed throughout. With her jagged silhouette, green ground cover and sharp peaks lost in low-hanging fluffy clouds, Moorea evokes the mystical landscape of “The Lord of the Rings.” She is mysterious, beautiful and wild, a perfect setting for the new home of a shipwreck survivor.

Marina Taina is located inside a lagoon lined by a coral reef, which makes it look like there is a surf break in the middle of the ocean that surrounds the many bobbing boats, with waves crashing and mist flying through the air in the distance. The water is two-toned: a darker ultramarine in the deeper sections where the boats are moored and a bright turquoise in the shallows near the reef, with bomboras and smaller coral gardens interspersed throughout. With her jagged silhouette, green ground cover and sharp peaks lost in low-hanging fluffy clouds, Moorea evokes the mystical landscape of “The Lord of the Rings.” She is mysterious, beautiful and wild, a perfect setting for the new home of a shipwreck survivor.

In contrast, the island of Tahiti, a mere 200 meters of ocean away, looks far busier with visible and audible car traffic, lit up homes that line the hills, roosters crowing and dogs barking. Lush palm trees line the edge of the island, and the homes stop about half-way up the steep mountains that look as though they are covered by a green carpet with intermittent clusters of trees. The sun is rising, slowly illuminating the light blue sky and its picturesque, fluffy pink clouds like cotton candy at a summer carnival. The light reflects off the water and the sight are truly a spiritual experience, evoking utter awe for Mother Nature and the Earth. Welcome to Tahiti, at last.

In contrast, the island of Tahiti, a mere 200 meters of ocean away, looks far busier with visible and audible car traffic, lit up homes that line the hills, roosters crowing and dogs barking. Lush palm trees line the edge of the island, and the homes stop about half-way up the steep mountains that look as though they are covered by a green carpet with intermittent clusters of trees. The sun is rising, slowly illuminating the light blue sky and its picturesque, fluffy pink clouds like cotton candy at a summer carnival. The light reflects off the water and the sight are truly a spiritual experience, evoking utter awe for Mother Nature and the Earth. Welcome to Tahiti, at last.

Grant’s momentary bliss was soon interrupted by the advancing sunrise, which began to illuminate the complete mess he found himself standing in. Hanavave looked beat up. Her rear bumpers were disintegrating, some of the stainless steel was rusting, a lot of the life preserving gear was ill kept, everything was dirty with a lot of mold, and there was stuff everywhere. There were multiples of everything, even if they were broken or no longer functioning. There was a tray full of maybe 100 pens. Similarly, another tray contained about 50 lighters, most of which were useless. Whatever parts were replaced, the old broken or dysfunctional ones were kept, stowed away in some obscure place.

Grant’s momentary bliss was soon interrupted by the advancing sunrise, which began to illuminate the complete mess he found himself standing in. Hanavave looked beat up. Her rear bumpers were disintegrating, some of the stainless steel was rusting, a lot of the life preserving gear was ill kept, everything was dirty with a lot of mold, and there was stuff everywhere. There were multiples of everything, even if they were broken or no longer functioning. There was a tray full of maybe 100 pens. Similarly, another tray contained about 50 lighters, most of which were useless. Whatever parts were replaced, the old broken or dysfunctional ones were kept, stowed away in some obscure place.

There were many items that didn’t belong on a relatively small boat with very limited space, like used wooden slats from a futon bed, propane gas bottles that had no connections, and the list goes on. The mattresses in the bunks were all moldy and unusable, and the cushions in the galley were misshapen and their zippers were broken. The trampoline was in bad shape, full of holes and barely holding on. The bimini window vinyl was so sun damaged that you couldn’t see through it and the gang plank looked like it had been through several hurricanes.

There were many items that didn’t belong on a relatively small boat with very limited space, like used wooden slats from a futon bed, propane gas bottles that had no connections, and the list goes on. The mattresses in the bunks were all moldy and unusable, and the cushions in the galley were misshapen and their zippers were broken. The trampoline was in bad shape, full of holes and barely holding on. The bimini window vinyl was so sun damaged that you couldn’t see through it and the gang plank looked like it had been through several hurricanes.

When Grant negotiated the contract, we knew that there were several items of deferred maintenance that we would be responsible for. We had a full survey done by an independent surveyor since we weren’t able to easily come to Tahiti to check the boat out ourselves, but unfortunately he didn’t uncover the full extent of the work necessary in order to prepare Hanavave for our long voyage to Australia. Of course, we weren’t naïve to think that the boat would be in tip top shape when we got here, but the fact that Grant and Jack came a week before Ellie, and I may have been the difference between a finalized boat sale and an abandoned voyage.

The boys arrived to Hanavave both exhausted and excited, but their first impression was that of shock once they saw the amount of stuff everywhere.

Ellie and Jana’s Stressful Departure

Ellie and my flight to Tahiti was exactly a week after Grant and Jack’s. We were still waiting on our ETIS forms, the individual applications we needed to complete in order to enter Tahiti, but we weren’t very stressed about them because we thought we’d either receive them the night before our departure like Grant did, or they were decommissioned altogether, as the U.S. Embassy representative told us over the phone. Our COVID PCR test appointments were on Wednesday afternoon and went off without a hitch, so apart from the elusive ETIS QR Code we had everything ready to go.

We flew from Seattle to San Francisco early in the morning and had a 4-hour layover before the Tahiti departure. The night before, I made sure to update the back end of all of our websites because I didn’t know how much internet access I would have once we arrived in Tahiti. As I gained more clarity of what I wanted to do over our many months of travel, I had passed all of my website work on to a friend, except of course our own and one other. The last website I was responsible for belonged to a friend. I had built it and maintained it for many years for free, because he was a friend and he’d periodically lend us heavy equipment or give us mulch for our front yard. It was a sort of trade and so I was happy to continue to work on the site as we traveled. My plan was to hand it over if internet access was too elusive.

We flew from Seattle to San Francisco early in the morning and had a 4-hour layover before the Tahiti departure. The night before, I made sure to update the back end of all of our websites because I didn’t know how much internet access I would have once we arrived in Tahiti. As I gained more clarity of what I wanted to do over our many months of travel, I had passed all of my website work on to a friend, except of course our own and one other. The last website I was responsible for belonged to a friend. I had built it and maintained it for many years for free, because he was a friend and he’d periodically lend us heavy equipment or give us mulch for our front yard. It was a sort of trade and so I was happy to continue to work on the site as we traveled. My plan was to hand it over if internet access was too elusive.

As luck would have it, his website crashed during a routine update, and I spent the hours of our layover in San Francisco trying to fix it. Unsuccessful, I emailed his secretary and my web designer friend explaining the situation and giving them all the necessary information to fix the site because at this point the best thing to do was to give it to someone who had the means to fix it.

By the time we arrived at our gate and lined up in the long line to get our documents checked, I was flustered and frustrated. I got my document folder out and when our turn came, all I heard was: “ETIS, please.” My blood pressure rose instantly. I took a breath and started to try to explain our ETIS story, and about how the U.S. Embassy told us that we didn’t need it and how my husband and son flew the week before and nobody asked them for it, and about how we have all of our covid requirements. But I didn’t get two words out and the gate agents cut me off and directed me to fill out the ETIS application again, which made absolutely zero sense. I called Grant in a panic, not knowing what to do. I filled out the ETIS forms again like they instructed me to, knowing full well that it was a futile exercise. I went back to try and plead with them again, at which point they very sternly told me that I was doing the wrong thing and that I needed to go somewhere else on the website to check the status of our ETIS. I thought: “The f-ing status is Pending, like I said in the beginning, when I showed you the screen shots that said ‘ETIS Pending,’ but you wouldn’t listen to me.” I was furious but tried to stay semi-calm and explain to them that the status said “Pending.” They still shooed me away to go find my ETIS status. It was embarrassing and by now, a bunch of people were just staring at Ellie and me, trying to navigate this circus.

I navigated the website to the status, which said “Pending” and walked back up to the table. By now, there was nobody left at the gate, and they were calling for all remaining passengers to board. There was now an additional man standing at the table, holding a walkie talkie and looking over the unhelpful man’s shoulder. As I approached, the original guy said: “You can go through, my boss says it is ok.” Relieved and furious at the same time, Ellie and I ran on to the fully boarded plane and sat down in our seats. I called Grant in tears, my voice still shaking, and he was also relieved beyond belief. I was so shaken that I bought WIFI for the whole flight just so I could communicate with him via WhatsApp while in flight.

I was so worried about getting a migraine after the stress we just experienced. Flying is already a recipe for disaster when it comes to my migraines, but now its chances were exponentially higher as all the stress hormones were doing their work on my body. I took a moment to take a breath and then turned to Ellie to commend her for staying completely calm, supportive and very helpful throughout our gate ordeal. As I was frantically filling out online forms, she was in communication with Grant troubleshooting our situation.

I was so worried about getting a migraine after the stress we just experienced. Flying is already a recipe for disaster when it comes to my migraines, but now its chances were exponentially higher as all the stress hormones were doing their work on my body. I took a moment to take a breath and then turned to Ellie to commend her for staying completely calm, supportive and very helpful throughout our gate ordeal. As I was frantically filling out online forms, she was in communication with Grant troubleshooting our situation.

I calmed down very quickly, and Ellie and I started to look at the movies that were available throughout our flight. I quickly found out that my entertainment screen wasn’t working but was so grateful to be sitting on the plane that it didn’t matter. Ellie and I would watch together and share hers. I also had a book I was enjoying so it would keep me busy the rest of the time.

We landed in Pape’ete, Tahiti about 8 hours later, exited the plane into the darkness and walked to the small airport terminal where everyone lined up for the next set of bureaucratic exercises. It was hot and humid, and we were wearing long everything. Ellie got very flushed very quickly and I worried she would faint from the heat. She also desperately needed to go to the bathroom, which was about 150 people, a COVID swab and an immigration interrogation away.

We landed in Pape’ete, Tahiti about 8 hours later, exited the plane into the darkness and walked to the small airport terminal where everyone lined up for the next set of bureaucratic exercises. It was hot and humid, and we were wearing long everything. Ellie got very flushed very quickly and I worried she would faint from the heat. She also desperately needed to go to the bathroom, which was about 150 people, a COVID swab and an immigration interrogation away.

About 45 minutes later, we got our brains swabbed and lined up at the immigration window. I stood nervously, trying to appear calm and friendly, while the agent looked over the forms I filled out on the plane. Suddenly he looked up and I froze, my eyes big with terror. “It says here you are staying at Marina Taina. Which boat? What’s the name of your boat?!” I almost peed my pants as I wrote “Hanavave” next to “Marina Taina.” “Ok, you can go.” And just like that, we were free! Mr. Christopher from the U.S. Embassy was right: the ETIS form was no more. But someone forgot to inform that man at the airport gate and he was too busy to see me as a fellow human, so he dug his heels in until his supervisor broke the news to him.

We found the bathroom, swiftly collected all four of our 50-lb on the dot bags filled with all kinds of equipment and some clothes and exited the airport as quickly as we could. Grant and Jack drove up in a little rental car which we were soon to turn into a clown car and as they got out to hug us, I lost it and started to cry.

It had taken so much to get here. We sold our home and everything else we could, we traveled all around the country, I had to leave my family, we even ended up having to leave the puppies, sold Thelma and Louise, the last semblance of home we had, organized and re-organized, shuffled and re-shuffled, wrestled with a logistical nightmare and finally we were here. This isn’t our final destination, but I now felt like our final destination was truly within reach for the first time. I was exhausted and relieved and so happy to have our family together again.

I navigated the website to the status, which said “Pending” and walked back up to the table. By now, there was nobody left at the gate, and they were calling for all remaining passengers to board.

Fixing Hanavave

By now we knew that Hanavave had a lot of deferred maintenance so there was much to be done to prepare her for our long voyage to Australia. Even though we are now in paradise, the first three weeks living on the boat were a big adjustment. We have been moored at Marina Taina, about 20 minutes outside of Pape’ete, the capital of French Polynesia. Trips to shore are made in “Dinky,” our trusty dinghy.

By now we knew that Hanavave had a lot of deferred maintenance so there was much to be done to prepare her for our long voyage to Australia. Even though we are now in paradise, the first three weeks living on the boat were a big adjustment. We have been moored at Marina Taina, about 20 minutes outside of Pape’ete, the capital of French Polynesia. Trips to shore are made in “Dinky,” our trusty dinghy.

There was so much to be done that Grant worked almost nonstop for three weeks, at times with the help of Jack, myself, Ellie, or Captain Alex, an extremely skilled local sailor who was beyond generous to us with his help and guidance in our first three weeks in Tahiti. His partner, Julie, works for the yacht brokerage we bought Hanavave from and has been equally as generous and helpful. Over the last four weeks, Alex and Julie have become our friends, and we are beyond grateful for them both.

In the mornings of the first few weeks, Grant usually made his way to the marina or into town in search of parts he needed for whatever project he was working on that day. He became fast friends with Michel, a French man in his 70’s who owns a workshop at Marina Taina. Michel has the reputation for being grumpy at times, but that’s only because he doesn’t suffer fools lightly. Grant’s kind and charismatic personality and his above average knowledge of anything and everything won Michel over right away. Grant still goes to see Michel daily and sometimes multiple times per day, and Michel always asks: “Did you break anything today?” Which really means: “What have you found to fix today?” From Michel to Captain Alex to another Alex the electrician, Grant quickly earned the respect of the locals with this impressive and wide set of skills. They call him “the mechanic.”

In the mornings of the first few weeks, Grant usually made his way to the marina or into town in search of parts he needed for whatever project he was working on that day. He became fast friends with Michel, a French man in his 70’s who owns a workshop at Marina Taina. Michel has the reputation for being grumpy at times, but that’s only because he doesn’t suffer fools lightly. Grant’s kind and charismatic personality and his above average knowledge of anything and everything won Michel over right away. Grant still goes to see Michel daily and sometimes multiple times per day, and Michel always asks: “Did you break anything today?” Which really means: “What have you found to fix today?” From Michel to Captain Alex to another Alex the electrician, Grant quickly earned the respect of the locals with this impressive and wide set of skills. They call him “the mechanic.”

Michel has the reputation for being grumpy at times, but that’s only because he doesn’t suffer fools lightly.

High Prices & A World-Traveling Crate

As one would expect, Tahiti is very expensive. Local prices are on average 30%-50% higher than in the U.S. A lot of things, especially boat parts or specialty items like cameras or drones are not available at all. Grant has gotten to know all of the hardware stores and marine supply places very well, often visiting each several times per week. We brought as many things as we could in our luggage, including an inverter, tools, snorkeling gear, hatch seals and wetsuits. Each of our bags was very close to the 50lb maximum allowed, which we made sure of with our trusty baggage scale.

As one would expect, Tahiti is very expensive. Local prices are on average 30%-50% higher than in the U.S. A lot of things, especially boat parts or specialty items like cameras or drones are not available at all. Grant has gotten to know all of the hardware stores and marine supply places very well, often visiting each several times per week. We brought as many things as we could in our luggage, including an inverter, tools, snorkeling gear, hatch seals and wetsuits. Each of our bags was very close to the 50lb maximum allowed, which we made sure of with our trusty baggage scale.

Additionally, we shipped a crate full of other important items such as a water maker, dive equipment and more tools via ship from Seattle to Samoa, thinking we would pick it up on our way to Australia. In the meantime, however, Samoa closed its port, and we were left with no choice but to reroute the crates through New Zealand and then on to Tahiti. This has of course turned out to be an expensive and time-consuming exercise. Theoretically, our crate should arrive in Tahiti in three weeks, but Julie informed us that a lot of Tahiti shipments have been stuck in New Zealand for six months or more now.

Local prices are on average 30%-50% higher than in the U.S.

Ever Changing Plans

Samoa is not the only port that is now closed. Apart from French Polynesia and American Samoa, every other major port we were planning to stop at is now closed to us. This includes Cook Islands, Tonga, Fiji, New Caledonia and Vanuatu.

While at first our plan was to leave Tahiti as soon as Hanavave was ready, we have changed our plans to stay here for another month or so. We have to wait and hope that our crate arrives from New Zealand so that Grant can fit the water maker to Hanavave. If the ports do not open by then, we will sail to Australia with one stop in American Samoa, which is about a 7-day sail from Bora Bora, the last stop in French Polynesia. We would re-provision in American Samoa and sail on to Australia, which is about a 20-day sail from there, making the water maker imperative.

Since this plan has much longer stretches of open water sailing, we have decided that in order to cover watches with at least one experienced sailor and reduce the stress overall we should add another crew member to our team. Jack, Ellie and I do not have any sailing skills and while we are learning, it will be important to have another highly skilled and experienced skipper on board. After a lot of searching for the right person, Grant found Evan from Boston. Evan is a highly experienced delivery skipper, which means that he delivers boats for a living. If our plan stays in place, Evan will join us in Tahiti in about three weeks.

While at first our plan was to leave Tahiti as soon as Hanavave was ready, we have changed our plans to stay here for another month or so.

Open Water Sailing & Trying Not to Die

When Grant first proposed that we get a boat and sail to Australia some months back, my immediate reaction was “no way.” With a very limited sailing experience that’s limited to island hopping in the Whitsunday Islands of Australia, open water sailing was an instantly anxiety inducing thought. It has never even close to entering my mind that I would voluntarily sail a great distance with no land in sight for days on end on a 38-foot boat. Such has been the reaction of over half of the people I know.

I have reasoned with myself that I’m afraid of open water sailing because I have never done it before. But people do it all the time, it’s safer than driving a car, and according to all first-hand accounts I’ve heard so far, it can actually be enjoyable. Julie always talks about how magical is can be do be doing your night watch shift, just you and the Milky Way, as vivid as it gets to the human eye, and dolphins or whales coming up to the boat to say hello.

There are also the first couple of test sails we did with Alex. First, we attempted to go to Makatea, an island about 24 hours away. We’d not only have to sail overnight, but we’d also have to sail against the wind to get there. Sailing against the wind is bumpy and more likely to induce sea sickness. We took off early in the morning and by mid-morning I felt like I was experiencing one of the worst hangovers of my life. Ellie was throwing up head (toilet) of the boat and bravely declaring “I’m ok, I’m ok,” while all I could do was to lay in the fetal position in the outside cockpit and do my best not to die.

Luckily, the wind changed, making our trip more like 36 hours long so Grant and Alex, our two captains, decided to change course and instead head for Mo’orea, a small island not far from Tahiti, still within sight, and reachable by 10 o’clock that night. Mercifully, it was also in the direction of the wind.

In the morning, I woke up deflated from yesterday’s experience but as soon as I went above deck and saw the jaw-dropping paradise we were anchored in, my spirits rose. The water was turquoise, and the mountains were green and mystical, straight out of “The Lord of the Rings.” Alex was adamant that in most cases, sea sickness only lasts for one to two days, three max, and then the system gets used to it and recalibrates itself.

On a later trip to Mo’orea, Ellie and I got sick again while sailing against the wind, but we both went below deck to change out of our wet clothes which was a big mistake. While we sat outside on the front deck’s trampoline, we both felt perfectly fine. It’s all about figuring out how your body responds to different situations and the different tricks you can employ to keep it at equilibrium. I do have to say, sailing without feeling sick is a pretty magical experience.

In the morning, I woke up deflated from yesterday’s experience but as soon as I went above deck and saw the jaw-dropping paradise we were anchored in, my spirits rose.

Sir David Attenborough

A couple of years ago, Grant and I watched “Planet Earth” and “Blue Planet,” the David Attenborough documentaries about the Earth and its oceans, and one of the things that stuck with me the most was French Polynesia and its vivid coral reefs. Marina Taina, where we are moored, is surrounded and therefore protected by a reef. The lagoon is filled with boats and some distance away, there is a break with waves splashing and spray flying as if from the middle of the ocean. On day one, the one thing we had to do was to go snorkeling, even though there was endless work to be done.

Sir David Attenborough did not lie. The snorkeling truly is like swimming in an endless aquarium. We’ve now snorkeled many times and even had a very rare encounter with a rather big, sleeping shark. All of a sudden, there she was, dozing at the bottom of the ocean snuggled up next to a bombora. And she looked like a real shark, not one of those little sharks that can often be seen swimming with the sting rays in the estuaries during low tide. When we told Julie about our shark sighting, she said with some astonishment that in the five years she’s lived in Tahiti, she’s only seen that type of shark twice. They are very elusive and more importantly, nothing to be scared of. These types of sharks are often referred to as the “dogs of the sea” and have no interest in humans, unless the humans are doing something stupid like cleaning fish and swimming in the guts.

Sir David Attenborough did not lie. The snorkeling truly is like swimming in an endless aquarium. We’ve now snorkeled many times and even had a very rare encounter with a rather big, sleeping shark. All of a sudden, there she was, dozing at the bottom of the ocean snuggled up next to a bombora. And she looked like a real shark, not one of those little sharks that can often be seen swimming with the sting rays in the estuaries during low tide. When we told Julie about our shark sighting, she said with some astonishment that in the five years she’s lived in Tahiti, she’s only seen that type of shark twice. They are very elusive and more importantly, nothing to be scared of. These types of sharks are often referred to as the “dogs of the sea” and have no interest in humans, unless the humans are doing something stupid like cleaning fish and swimming in the guts.

Alex took us snorkeling to a special spot in Mo’orea where we drifted with the current almost a mile back to the boat through some spectacular coral gardens with beautiful aquarium fish, Nemo and Dori included. We even saw some eagle rays, which look like large birds flying through the ocean with the utmost grace. I’ve never seen anything like it and at that moment, all that sea sickness was worth it.

Sir David Attenborough did not lie. The snorkeling truly is like swimming in an endless aquarium.

“No Shoes, No News.”

As the days went by and Grant’s projects began to ease off a bit, things got easier. At first, I did a lot of cleaning on the boat, but there is only 38 feet of her so eventually the deep cleaning was done, and I felt about as useful as a water maker in Samoa. Alex skippers a lot of charter trips, for which he has developed a very important saying: “No shoes, no news.” This means that there are no shoes on the boat and also no internet, which in turn means no news.” Boat activities pretty much involve cooking, cleaning, reading, meditating, some boat friendly exercise, swimming and playing games. Ours are currently limited to Uno and Bananagrams, with more hopefully on their way in a crate from Samoa. Watching Grant work all day while I was reading didn’t exactly feel comfortable, so once the constant work ceased a little, we were able to take a breath and start to adjust a little.

As the days went by and Grant’s projects began to ease off a bit, things got easier. At first, I did a lot of cleaning on the boat, but there is only 38 feet of her so eventually the deep cleaning was done, and I felt about as useful as a water maker in Samoa. Alex skippers a lot of charter trips, for which he has developed a very important saying: “No shoes, no news.” This means that there are no shoes on the boat and also no internet, which in turn means no news.” Boat activities pretty much involve cooking, cleaning, reading, meditating, some boat friendly exercise, swimming and playing games. Ours are currently limited to Uno and Bananagrams, with more hopefully on their way in a crate from Samoa. Watching Grant work all day while I was reading didn’t exactly feel comfortable, so once the constant work ceased a little, we were able to take a breath and start to adjust a little.

This means that there are no shoes on the boat and also no internet, which in turn means no news.

Powered by the Sun & Wind

Apart from “No Shoes, No News,” Hanavave is also not plugged into an external power source. This means that while we’re moored, we are relying on solar and wind power for our electricity and if we want to charge an electric toothbrush, or a computer, it’s best done at noon when there is the most sun, provided that it’s out in the first place. There are alternators on the engines (Grant fitted two brand new 125Amp alternators very early on when he realized the charging circuits were cactus) that can generate power and recharge the batteries, but you need to start the engines and run them for an extended period to get the benefit.

Apart from “No Shoes, No News,” Hanavave is also not plugged into an external power source. This means that while we’re moored, we are relying on solar and wind power for our electricity and if we want to charge an electric toothbrush, or a computer, it’s best done at noon when there is the most sun, provided that it’s out in the first place. There are alternators on the engines (Grant fitted two brand new 125Amp alternators very early on when he realized the charging circuits were cactus) that can generate power and recharge the batteries, but you need to start the engines and run them for an extended period to get the benefit.

There is also no air conditioning on Hanavave, so Grant installed little fans in each cabin so that we can sleep comfortably at night. Because we are in the southern hemisphere, it is currently winter, or the dry season in French Polynesia. This means very consistent temperatures ranging between the late 70’s to the mid 80’s with humidity around 70-80% and 60’s to 70’s at night. With a breeze, this can all feel quite comfortable, but with the air still and the sun out, you are baking in no time. This is where Alex’s second saying comes in handy: “The swimming pool is open!” The water temperature is around 80 degrees, which makes for a very pleasant swimming pool, minus the harmless sharks. 😉

The swimming pool is open!

Showers, Dishes & Laundry

Water is another scarce commodity on Hanavave: we have two 180-liter water tanks on board (about 80 gallons total), which is not a lot for 4 people. Showers were out of the question from the outset, but we quickly figured out that dishes were going to be washed in the ocean, too. No, our coffee does not taste salty in the morning, but I was wondering the same.

Water is another scarce commodity on Hanavave: we have two 180-liter water tanks on board (about 80 gallons total), which is not a lot for 4 people. Showers were out of the question from the outset, but we quickly figured out that dishes were going to be washed in the ocean, too. No, our coffee does not taste salty in the morning, but I was wondering the same.

We use our swims to wash our bits and pits and about once a week or so, we take showers at the marina. They are the kind where you push a button and cold water comes out for about 30 seconds, so they make you appreciate the bougie shower you used to have at home and also wonder if you’ve been taking too long of a shower all along.

Laundry gets done about once or twice a week at a cool $9 per load. And that’s just for the washing machine, not the dryer. Luckily, boats are great for hanging clothes out and airing them, so we try and do as little washing as possible.

Showers were out of the question from the outset, but we quickly figured out that dishes were going to be washed in the ocean, too.

Antifouling. It’s Not What You Think.

One of the biggest jobs we had to do on Hanavave was antifouling, which required us to pull her out of the water at a dry dock. Antifouling involves power washing and lightly sanding the bottom of a boat all the way up to its waterline and then applying antifouling paint, which prevents barnacles and crustaceans from attaching themselves for a free ride. It is an important part of boat maintenance, and some countries require that a boat has been antifouled within a certain amount of time in order to enter its borders. Australia is one of those countries.

We set off from Marina Taina at 6am to get to the dry dock, which was about an hour away in Pape’ete. On the way, we passed the airport which requires you to get permission from the port captain to cross because sometimes the boat masts can interfere with air traffic. Once we arrived at the dry dock, a swimmer positioned two large belts under Hanavave, and a big boat lift raised her out of the water.

We set off from Marina Taina at 6am to get to the dry dock, which was about an hour away in Pape’ete. On the way, we passed the airport which requires you to get permission from the port captain to cross because sometimes the boat masts can interfere with air traffic. Once we arrived at the dry dock, a swimmer positioned two large belts under Hanavave, and a big boat lift raised her out of the water.

Once she was up, the lift drove her to shore where she got propped up on blocks. One of the dock workers then did the power washing part and we decided to pay for the sanding and let them do it as well, because we did not have the appropriate equipment and it would have taken us a very long time, not to mention broken our necks.

Antifouling involves power washing and lightly sanding the bottom of a boat all the way up to its waterline and then applying antifouling paint, which prevents barnacles and crustaceans from attaching themselves for a free ride.

Ia orana!

The dry dock is a hustling and bustling place. There are about 100 workers working on various boats, doing everything from antifouling on much larger vessels to building big aluminum fishing trawlers. Most of the guys are native Polynesian and I loved their demeanor. They always acknowledge you with a big smile on their face and a friendly, “Ia Orana,” the Polynesian greeting that is ubiquitously used on the island. They are genuinely nice people and seem generally happy.

In the afternoon, Ellie and I walked to the hardware store to pick up extra paint rollers for the boys and on our way back, the shift at the dock was ending. The men were all communing by their cars or mopeds parked on the narrow street adjacent to the dry dock, having a good time catching up with each other. The mood was very jovial with some playing music and others laughing. As we walked through the suddenly crowded street, we received more smiles and “Ia Orana” than we could keep up with and felt very welcome by everyone.

They always acknowledge you with a big smile on their face and a friendly, “Ia orana,” the Polynesian greeting that is ubiquitously used on the island.

More Antifouling

While Hanavave was being sanded, we were busy fixing up botched repairs and removing rusted bolts, disintegrated bumpers, and filling holes with epoxy. It was a pretty hot day, so we knew that this work would not be pleasant. Once the sanding was finished, it was Grant and Jack’s turn to apply the antifouling paint. The paint is toxic and difficult to apply, which is why the boys had to change into their “Breaking Bad” outfits and wore respirators. While they painted, Ellie and I worked on restoring our gang plank, which looked like it had survived multiple hurricanes. We sanded and stained it, which made it look like it had survived multiple hurricanes but then got sanded and stained. Whatever, we were still proud of our handiwork and most importantly, we weren’t relegated to watching Grant and Jack work their butts off while we sat around fanning ourselves.

While Hanavave was being sanded, we were busy fixing up botched repairs and removing rusted bolts, disintegrated bumpers, and filling holes with epoxy. It was a pretty hot day, so we knew that this work would not be pleasant. Once the sanding was finished, it was Grant and Jack’s turn to apply the antifouling paint. The paint is toxic and difficult to apply, which is why the boys had to change into their “Breaking Bad” outfits and wore respirators. While they painted, Ellie and I worked on restoring our gang plank, which looked like it had survived multiple hurricanes. We sanded and stained it, which made it look like it had survived multiple hurricanes but then got sanded and stained. Whatever, we were still proud of our handiwork and most importantly, we weren’t relegated to watching Grant and Jack work their butts off while we sat around fanning ourselves.

Our favorite part of the dry dock was meeting a very cute, sweet little puppy we named “Skippy,” because he was the same color as the peanut butter. When we arrived, Skippy was cowering in some scaffolding on the edge of the dock, shaking in fear and unwilling to come out. But Jack and Ellie have a way with puppies and soon enough, Skippy was out of the scaffolding and playing with them as though he’d been their dog since always. He was so playful and affectionate and made that hard day’s work go by so much more joyfully. We fed him tuna and while he ate it, he was far more interested in what Jack was doing or where he was going. We all knew that leaving the next day would be very hard.

Our favorite part of the dry dock was meeting a very cute, sweet little puppy we named “Skippy,” because he was the same color as the peanut butter. When we arrived, Skippy was cowering in some scaffolding on the edge of the dock, shaking in fear and unwilling to come out. But Jack and Ellie have a way with puppies and soon enough, Skippy was out of the scaffolding and playing with them as though he’d been their dog since always. He was so playful and affectionate and made that hard day’s work go by so much more joyfully. We fed him tuna and while he ate it, he was far more interested in what Jack was doing or where he was going. We all knew that leaving the next day would be very hard.

The paint is toxic and difficult to apply, which is why the boys had to change into their “Breaking Bad” outfits and wore respirators.

Sailing to the Moon

We spent that night aboard Hanavave at the dry dock. It was a very windy night, and she shook as she was propped up on large blocks on land. It was hard to sleep, because it felt like she was going to take off at any moment and fly all the way to the Moon. Luckily, Hanavave decided to stay on Earth, at least for now, and we woke up ready to finish out our stint at the dry dock. We got a nice good morning greeting from Skippy, who was patiently waiting for us to wake up, descend the ladder and give him some love.

We were told that they would be putting Hanavave back in the water at 11am, so Grant worked on the bumpers, and I spent about 2.5 hours cleaning the decks because they were covered in a black dust from all the other boats around us being sanded. It was unbelievable, as the whole boat was covered in a black film and since I couldn’t use a hose, I was relegated to a small bucket of water and a rag, crawling on my hands and knees to wipe everything down. I’m pretty sure that by the time I was finished, a whole new layer of dirt was covering the boat, as if to laugh at my silly and pointless OCD attempt at cleaning it. It was a good lesson, but it could have been kinder to my body.

True to their word, the crew lowered us back into the ocean around 11am and we were on our way back to our mooring at Marina Taina soon thereafter. Skippy was there to say goodbye, wagging his tail and making it really hard to leave without him. As we hovered above the water, still above land, one of the workers asked us if Skippy was our dog. I told him that he wasn’t, but that he was now his dog and that he had to take him home and take care of him. He agreed and we choose to believe that he fulfilled his promise because each time Grant returned to the dry dock thereafter, Skippy wasn’t there.

Skippy was there to say goodbye, wagging his tail and making it really hard to leave without him.

All the Bread

On to more pleasant topics.

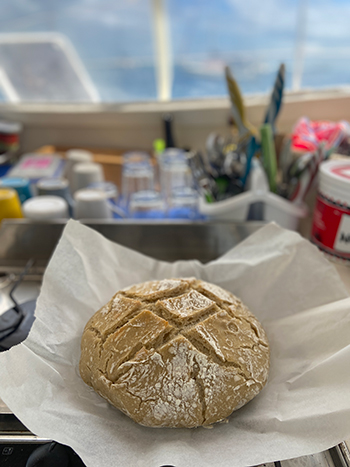

In preparation for a potentially very long time at sea, we have decided that it may be a good idea to perfect a bread recipe. We have a 3-burner gas stove and a small oven on board, so the potential for success is there. After some searching, we found a simple bread recipe that was in metric measurements to accommodate the measuring cups we have on board. We also decided to create a makeshift Dutch oven out of a stainless steel pot in order to maintain the moisture of the bread.

In preparation for a potentially very long time at sea, we have decided that it may be a good idea to perfect a bread recipe. We have a 3-burner gas stove and a small oven on board, so the potential for success is there. After some searching, we found a simple bread recipe that was in metric measurements to accommodate the measuring cups we have on board. We also decided to create a makeshift Dutch oven out of a stainless steel pot in order to maintain the moisture of the bread.

A pleasant smell of baking bread wafted through the boat, but we were nonetheless in trepidation of the final product. The oven does not get as hot as it’s supposed to, so we extended the prescribed baking time and hoped for the best. When the time came, we pulled the bread out of the oven and voilà, it was not only beautiful but also delicious! We’ve been baking bread daily ever since, because a loaf will not last more than a day. We are now experimenting with adding herbs and making sourdough. We know fresh bread will be a real treat when we’re at sea, so we’re honing our skills in advance.

When the time came, we pulled the bread out of the oven and voilà, it was not only beautiful but also delicious!

Tahiti from Within

After almost four weeks in Tahiti, we rented a car to go explore the island from within. There is about a 120-km road that circumnavigates the island, and it is equally as beautiful whether you look left or right. Depending on the direction you drive on one side you’ll have the oceanfront with its dark, volcanic beaches and endless ocean to the horizon. On the other side there is lush bright green foliage and palm clad mountains, valleys and amazing waterfalls peppering the drive. It took only a few hours to circumnavigate Tahiti and it was so well worth it.

After almost four weeks in Tahiti, we rented a car to go explore the island from within. There is about a 120-km road that circumnavigates the island, and it is equally as beautiful whether you look left or right. Depending on the direction you drive on one side you’ll have the oceanfront with its dark, volcanic beaches and endless ocean to the horizon. On the other side there is lush bright green foliage and palm clad mountains, valleys and amazing waterfalls peppering the drive. It took only a few hours to circumnavigate Tahiti and it was so well worth it.

There is about a 120-km road that circumnavigates the island, and it is equally as beautiful whether you look left or right.

Diving Deep

Since we are staying in Tahiti for another month and have a couple of scuba tanks coming in our world-traveling crate, Ellie and I decided to try scuba diving in hopes of loving it and wanting to get certified while we’re here. We really enjoy snorkeling, so scuba diving should be a natural progression. Jack has already done an introductory dive a few years ago in Mexico, so he would join us in the certification process on the second dive. In order to get a PADI certification, you have to complete 7 dives and an online course. Grant is already certified, but he would join us on a few dives.

Grant booked us an introductory dive and we set off on the dive boat, together with another 20 people or so. Our instructor, Roman, who was going to dive with just us, was a very nice & handsome French man and his English was very good. Once we got to the dive site, Roman explained a few things about the equipment, gave us very clear instructions on what to do when and taught us the hand signals used for communication under water.

Next, he hoisted the heavy dive tanks onto our backs, we shimmied our way back as close to the edge of the boat until the weight of the tanks pulled us down into the ocean. We both bobbed up laughing, as the whole maneuver felt very ungraceful and looked as though a couple of sacks of potatoes fell overboard.

Roman took us down one at a time and I went first. We were only going down to about 5 meters to make sure we could clear our sinuses and adjust to breathing through the regulator. My first attempt was unsuccessful. My ears weren’t clearing, causing them to hurt and I felt like I couldn’t breathe, which induced a slight panic. I gestured to Roman to go back up and in a few seconds, our heads were back above water. I told him what my problems were, and he gave me more ways to clear my ears. He assured me that the difficulty breathing is normal and will go away very quickly.

As a child, I had severe asthma and would often find myself unable to breathe. The trauma of not being able to breathe at times as a child was still wired in a neuropathway in my brain. The experience of not being able to properly breathe under water felt very similar to an asthma attack, so a subconscious response was triggered, and I started to feel panicky. From now on, each time I dive and let my body know that in reality the sensation doesn’t signal imminent death, the neuropathway will eventually re-wire and the trauma will be healed.

I was able to successfully go down on the second try and now it was Ellie’s turn. There was a moment of apprehension when Roman left me down there alone, but I decided to be brave ;-). Ellie came down without any problems, so we headed off into deeper water. Roman was right, in a very short amount of time, my breathing settled, and I felt completely fine. We dove around coral gardens and saw all the amazing colorful fish close up. There were parrotfish, angelfish, wrasse, butterflyfish, surgeonfish, damselfish, triggerfish and others. We spent about 10 minutes playing with a very cute and very curious triggerfish that very comically tried to steal a Tahitian black pearl out of Roman’s bracelet.

We also explored a small plane wreck and two boat wrecks. A funny addition to the dive site was a school desk with a lamp and an open MacBook computer. Just in case the fish need to check their emails. It was awesome to be a part of a whole new world for the first time. Both Ellie and I were moved by the experience and came back excited for the diving certification. We are really looking forward to sharing it with Grant and Jack.

There were parrotfish, angelfish, wrasse, butterflyfish, surgeonfish, damselfish, triggerfish and others.

What’s Next

One thing’s for sure: We will have to stay flexible in order to ensure that our trip is safe and manageable. Most ports remain closed so right now our plan is based around this scenario. This means that we will have to sail with fewer stops, which right now is down to only one, meaning far more consecutive days at sea. In order to safely and comfortably do this, we need another crew member. Right now, we plan on having Evan, a sailor from Boston, come down to Tahiti and make the trip with us.

But first, we have to wait for our world-traveling crate to arrive from New Zealand. Once it’s here, Grant will install the water maker and Hanavave will be 100% ready to set off. We are hoping that the shipping system is reliable, and our crate is delivered within the next three weeks or so. In the meantime, we will complete our diving certifications, make more small repairs on the boat, bake more bread, enjoy Tahiti and Moorea and the fact that we don’t have to be anywhere at any time.

Travel with us:

Travel Diary

Travel

Day 225: Travel Day | Wenatchee to Seattle, WA

Wednesday, June 9, 2021Travel Day: Wenatchee to Seattle, WATOTAL MILES TRAVELED: 10,366Photo GalleryClick image to enlarge.Video GalleryTravel with us:Travel DiaryTravelThis is a daily log and photos of...

Day 224: Wenatchee, WA

Tuesday, June 8, 2021Wenatchee, WATOTAL MILES TRAVELED: 10,035Photo GalleryClick image to enlarge.Video GalleryTravel with us:Travel DiaryTravelThis is a daily log and photos of what we're up...

Day 223: Wenatchee, WA

Monday, June 7, 2021Wenatchee, WATOTAL MILES TRAVELED: 10,035Photo GalleryClick image to enlarge.Video GalleryTravel with us:Travel DiaryTravelThis is a daily log and photos of what we're up...

Related Articles

Related

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

TRAVEL WITH US!

We are currently sailing the South Pacific to Australia.

Thank you for joining us, have a great day!